Labor South

looks at film and culture as well as politics, and thus here is an article I recently published in the amazing online film magazine, Vague Visages

, about the making of the 1956 noir film The Killing

. Directed by Stanley Kubrick, the film was co-written by the legendary hardboiled writer Jim Thompson, an Oklahoma Territory native and former IWW/Wobbly who became the first of many writers the would-be auteur Kubrick shamefully cheated or tried to cheat out of their proper writing credits. The film's marvelous cast is a Who's Who of great character actors, the working stiffs of the Big and Small Screen, long a fascination of yours truly. This is a tribute to them as well as to film noir and Jim Thompson. A link to the Vague Visages

article is also below. https://vaguevisages.com/2023/03/24/the-killing-essay-stanley-kubrick-movie-film/

I can see it just as clearly as if it had really happened.

The gathering at the table midway down the left aisle at Hollywood’s Musso

& Frank Grill is getting emotional.

They’re hovering over their cigarettes, their glasses of bourbon and

wine and beer, their half-eaten plates corned beef and cabbage, chicken pot

pie, and sauerbraten.

A waiter whispers to Gustav Hasford and points to a table

across the room. “That’s where Faulkner sat,” the waiter says, knowing this is

Hasford’s first time at Musso & Frank. The Alabamian nodded appreciatively.

The other writers at the table—Jim Thompson, Calder Willingham, Frederic

Raphael, Terry Southern, and Dalton Trumbo—have been here a thousand times.

“He thought you were verbose and self-important,” Raphael

says to Trumbo.

“And you know what Kirk Douglas said about him,” Trumbo

answers after another sip of his wine. “He’s `not a writer.’ He’s `a talented

shit’ who tried to steal credit for my screenplay and keep me on the

Blacklist.”

“He gave me some of that same strange love, too,” Southern

rejoins.

“He nearly ruined my film trying to rewrite it,” Willingham

says. “The auteur. It was all him and nobody else, whether he deserved it or

not.

Hasford drinks deep into his Budweiser. “He and Michael Herr

wouldn’t even let me meet with them, and I not only helped write the script, I

wrote the goddamn book.”

“Directors are often unpunished serial killers who

appropriate credit from writers whom they have jettisoned,” Raphael says.

Big Jim Thompson waves a big paw, polishes off his whiskey

and motions to the waiter for another. He leans across the table, long-held anger

and hurt and resentment embedded in his rutted face. “You all came after me. I was the first he

betrayed. You fellows just followed in my footsteps.”

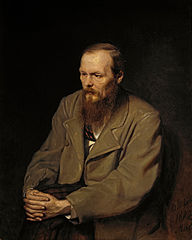

(To the right, Jim Thompson)

Hardboiled writer Jim Thompson never forgave director

Stanley Kubrick for denying him screenwriting credit in the 1956 noir

masterwork The Killing. It was just

one of many historic precedents of Kubrick’s first major feature film.

Hailed by Noir Czar Eddie Muller as “a monument to the

classic caper film and a fresh gust of filmmaking in one clever package,” The Killing would go on to influence

filmmakers ranging from those of the French New Wave to New Hollywood

filmmakers like Martin Scorsese to today’s Quentin Tarantino.

The Killing also marked

a special moment in film history. It heralded the arrival of a film world

enfant terrible. It featured a collection of some of film’s greatest character

actors, a star wrestling with deep self-contempt for his earlier testimony

before the U.S. House for Un-American Activities Committee, and a compelling

story of a racetrack heist that becomes an existential probe into the meaning

of life.

Even 67 years after its release, The Killing resonates. Tarantino talks about the “non-linear plot,”

how The Killing “changed the movies

you love.” This low-budget—it cost $320,000 to make—box office failure “boldly”

announced “the stylistic and thematic preoccupations that would become

important constants” in Kubrick’s career, Haden Guest writes in an essay for

the Criterion edition of the film. Scenes like Johnny Clay hiding a gun in a

flowerbox later inspired a similar scene in The

Godfather. The mask Johnny uses during the heist shows up later in films

like Batman: The Dark Knight (2008). Timothy Carey’s sharpshooter, though hidden

from view, is even among the crowd on the cover of the Beatles’ album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

(Stanley Kubrick)

The Killing

anticipated the films of the French New Wave—and with “its jagged time

structure and doubling back over past events” marks Kubrick as not only “a bridge

between the studio genre picture and the European art film” but as a “key

transitional figure between Old and New Hollywood,” Guest says.

(Marie Windsor and Elisha Cook Jr.)

Casting was another key to the genius that was The Killing. No noir film ever boasted a

greater gathering of character actors—Elisha Cook Jr., Jay C. Flippen, Ted de Corsia,

Timothy Carey, Marie Windsor, and Coleen Gray. Sterling Hayden got the lead

role as Johnny Clay after Frank Sinatra never could commit to a film version of

the Lionel White novel Clean Break

that became the basis for The Killing.

The studio, United Artists, wanted Victor Mature, but Kubrick and producer

James B. Harris refused to wait the eighteen months Mature needed before he

became available. They got Hayden for

$40,000, but the studio then only committed $200,000 to the project. Harris had

to raise the rest from his own savings account plus a loan from his father.

Hayden’s performance was masterful, and driven in part

perhaps by the inner tensions that had always created misgivings about choosing

acting as a career, tensions then exacerbated by the former seaman’s caving and

naming of names of suspected Communist sympathizers before the House for

Un-American Activities Committee. He had briefly joined the Communist Party

after fighting with the Partisans in Yugoslavia during World War II.

(To the right, Sterling Hayden)

“The sense of disturbance prevails—deep-set, its roots in

self-contempt,” he writes in his autobiography Wanderer. “I’ve lived with such torment for years and maybe I

always will.”

In the film, Hayden’s Johnny Clay has just gotten out of

prison and believes he has a plan for the perfect crime, a $2 million heist at

a racetrack. What’s perfect, he believes, is the fact he’s assembled a five-man

team of non-criminals, including a cop, a wrestler buddy, sharpshooter, and one

of the window tellers at the racetrack, none of whom would likely raise

suspicion from the law. His sharpshooter Nikki Arcane, played by Timothy Carey,

is assigned to shoot the lead horse in the race, creating enough havoc to allow

Clay and the others to pull off the heist.

(Timothy Carey)

The weak link proves to be the window teller, who lets his

cheating wife find out enough about the plan to tip off her gangster lover. The

lover decides he wants that $2 million and ends up in a deadly shooting match

with Johnny’s team. Johnny manages to slip away with the loot and his

girlfriend but before they can fly away they see the suitcase carrying the

money fall off the airport baggage wagon and two million dollars scatter in the

wind across the tarmac.

It was a chance meeting on a New York City street between Harris

and Kubrick, both in their mid-twenties at the time and still fledglings in

filmmaking, that planted the seed that became The Killing. Kubrick was a

former Look magazine photographer who

had turned to film and had a couple low-budget minor films to his credit,

including the feature film Killer’s Kiss,

a noir with haunting and promising cinematography but amateurish dialogue and

plot.

“The Killing, a

brilliantly paced story about a racetrack robbery, is the work of a

professional filmmaker,” writes Foster Hirsch in his book The Dark Side of the Screen. “Killer’s

Kiss, that of a talented amateur.”

James B. Harris had made training films for the Signal Corps

during the Korean War. A founder of Flamingo Films, he learned about Stanley

Kubrick from his partner and fellow Signal Corps member Alexander Singer, who

invited Kubrick to the set of a film they were making after the war. Harris

would go on to work as a producer with Kubrick not only on The Killing but also Paths of

Glory (1957) and Lolita (1962)

before pursuing his own career as a director.

It was Harris who found the crime novel Clean Break by Lionel White in the Scribner’s Bookstore on New

York’s Fifth Avenue and decided it would be a great vehicle for the new company

he and Kubrick had just formed, Harris-Kubrick Pictures. He liked the book’s

flashbacks and unusual nonlinear structure. He gave it to Kubrick, who agreed

and asked Harris to pursue getting the rights for it. They learned that the Los

Angeles-based Jaffe Agency was already negotiating with Frank Sinatra for a

film version, but no decision had been reached. Harris bought the rights with

$10,000 out of his own pocket.

After getting United Artists on board to back the project,

Kubrick, an avid reader and lover of literature, suggested crime novelist Jim

Thompson as a writer for the script. Thompson today is a legend in the

hardboiled world of noir—a former IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) Wobbly

and author of chilling tales such as The

Killer Inside Me--but at the time he was on a downward, alcoholic spiral

working at tabloids and strapped for cash. “Stanley Kubrick rescued Thompson

from an early retirement into hackdom,” writes Robert Polito in his 1995

biography of Thompson, Savage Art.

Thompson, unfamiliar with the screenplay format, went to

work for Harris and Kubrick. They worked at their company’s 57th

Street office before Thompson migrated to a nearby hotel.

“Jim Thompson had made him nervous when they were working

together on The Killing,” writer

Michael Herr recounts in 2000 memoir Kubrick,

“a big guy in a dirty old raincoat, a terrific writer but a little too

hard-boiled for Stanley’s taste. He’d turn up for work carrying a bottle in a

brown paper bag, but saying nothing about it—it was just there on the desk with

no apology or comment—not at all interested in putting Stanley at ease except

to offer him the bag, which Stanley declined, making no gestures whatever to

any part of the Hollywood process, except maybe toward the money.”

One of the first big hurdles in the project was the fact no

racetrack would agree to be the setting of a movie about a racetrack grand

robbery. Kubrick’s biographer Vincent LoBrutto writes about this. Knowing it

was be impossible to secure such an agreement, “sets were being designed and

built for the interior sequences. Other exterior sequences could be achieved

using second-unit footage and rear-screen projection.” Still, an agreement was

reached with San Francisco’s Bay Meadows Racetrack to allow the filming of

“second-unit material of a race in progress.”

Union restrictions (Kubrick could not both direct and be

director of photography) forced camera-savvy Kubrick to hire veteran

cinematographer Lucien Ballard. He and Ballard locked horns a number of times

during the filming, however, as Kubrick challenged Ballard’s time-honed methods

with untested innovations, such as using a hand-held camera and a 25mm lens for

certain shots when Ballard wanted a more standard 50mm lens. However, Ballard’s

contributions made the film better, Haden Guest writes. “Ballard’s diagrammatic

hot-spot lighting transforms dingy apartments and hidden back rooms into

dramatic extensions of the robbers’ feverishly claustrophobic lives,” and it

points to elements seen in future Kubrick films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and The Shining (1980).

(To the right, Ted de Corsia)

The supporting cast of The

Killing is a Who’s Who of noir character actors. Elisha Cook Jr. firmly

established himself as a founding father of Noir World in his role as the gunsel

Wilmer Cook in John Huston’s The Maltese

Falcon in 1941. Further roles such

as hopped-up jazz drummer Cliff March in Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady (1944) cemented his status. Ted de Corsia, who plays

corrupt policeman Randy Kennan, looks “like a guy who’d spent his whole life in

boxing gyms and bookie joints” with his barrel chest, beady eyes, and “hair

glistening with a hard shell lacquer of Wildroot Cream,” writes Eddie Muller in

his 1998 book Dark City: The Lost World

of Film Noir.

Timothy Carey’s sharpshooter character, Nikki Arcane,

completes his task of killing the thoroughbred Red Lightning in the race

allowing Johnny Clay’s gang to do the heist. However, his surly, racist

behavior toward the African American parking attendant sets the stage for his

own ultimate demise. “Played with reptilian charm,” as Haden Guest describes

the performance, Carey’s Nikki Arcane “leers and grunts and groans out of his

permanent death-mask face,” writes Barry Gifford in his 1988 book, Out of the Past: Adventures in Film Noir.

Carey was one of the most unusual of Hollywood character

actors. Notorious for scene-stealing and his unexpected improvisations—such as

his extended crying and moaning “I don’t want to die” during the execution

scene in Kubrick’s Paths of Glory

(1957)—he had one of those “difficult to

work with” reputations in Hollywood, yet directors from Kubrick to Cassavetes

to Coppola to Tarantino recognized his talent and repeatedly sought him out for

supporting roles in their films.

“He was unrivaled in the 1950s in expressing his nuttiness

in unexpected ways,” Eddie Muller says.

Marie Windsor and Coleen Gray provide the feminine challenge

to all the testosterone in the film. Gray is Johnny Clay’s long-suffering

girlfriend. Gray brought noir credits to the cast with roles in classics like Kiss of Death (1947) and Nightmare Alley (1947), but she was “always

the lone ray of light in noir’s dismal demimonde,” according to Muller, the

lone good girl amid a crew of criminal ne’er-do-wells.

Windsor’s Sherry Peatty is the classic femme fatale, the

cheating, scheming wife of Elisha Cook Jr.’s

henpecked cuckold George Peatty, yet another gem of a role that

established Cook as “the avatar of weak-willed weasles,” in Eddie Muller’s

estimation. Windsor’s noir credits

included Force of Evil (1948) and The Narrow Margin (1952).

(Kola Kwariani)

Add to these other cast members such as Jay C. Flippen as

the heist’s homosexual underwriter Marvin Unger, Kubrick’s chess-playing buddy Kola

Kwariani as strongman Maurice Oboukhoff, and, of course, Sterling Hayden, whose noir

creds included his role as Dix Handley in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950), and you’ve got what Eddie Muller calls

“a hand-picked rogue’s gallery,” and “ample proof that Stanley Kubrick loved

film noir.”

The film was shot quickly—less than the 24 days scheduled--in

Los Angeles on an independent’s budget with UA providing only $200,000. Kubrick

took no salary and lived off loans from Harris. Kubrick’s directing—the

27-year-old director had never acted himself--was largely low-key. “He didn’t direct in front of anybody else,’

Marie Windsor recalled. “He’d say, `Marie, come over here a minute.’ We’d go

behind the scenery, and he’d say, `In this scene, I want you to be really tired

and lazy.’ I’d had some stage training, and he was trying to get me not to use

my big voice.”

Once filming ended, Hayden’s agent, Bill Shiffren, and other

industry previewers weren’t impressed and insisted Kubrick re-shoot the film in

a more traditional linear fashion. Kubrick re-edited it, but he and Harris

decided they had to go with their original version, which more closely matched

the structure of Lionel White’s book.

“We put it back the way we had it at the preview and delivered it that

way to United Artists,” Harris later recalled.

With a score that featured André Previn on piano and Shelly

Manne on drums, the re-constituted film got through UA executives, but the

studio released the film on May 20, 1956, earlier than scheduled and with

minimal publicity. Plus the studio gave it second billing in a double feature

with Bandido starring Robert Mitchum

on top. The Killing thus got little attention and lost money, but it caught

Hollywood’s eye. MGM’s Dore Shary liked it enough to bring Harris and Kubrick

under his studio’s wing for future productions, and the following year it led

to a huge career boost for Kubrick with the director’s job for the war film Paths of Glory (1957) starring Kirk

Douglas.

The Killing would

prove pivotal to Kubrick’s career. Douglas had seen the film and “was so taken”

by it that he asked to meet Kubrick, who also wanted Douglas for the lead role

of Colonel Dax in Paths of Glory. The Killing “was an unusual picture, and

the studio had no faith in it and handled it poorly,” Douglas writes in his 1988

autobiography The Ragman’s Son. “I

was intrigued by the film, and wanted to meet the director.”

Douglas, a big star at the time, was key in helping to get

financing for Paths of Glory. He told

Kubrick the film was important and needed to be made even though it was unlikely

to turn a profit. During filming, he was impressed with Kubrick’s talent but

also found him frustrating. Kubrick tried to change the screenplay written by

Calder Willingham and Jim Thompson—whose anger at Kubrick over the credits in The Killing didn’t prevent him from

signing on to another film with him—and turned “a beautiful script” into a “cheapened

version” with dialogue that was “atrocious.” When confronted by Douglas about

the changes, Kubrick retorted, “I want to make money.”

Douglas said Kubrick’s rewritten script included lines like

“You’ve got a big head. You’re so sure the sun rises and sets up there in your

noggin you don’t even bother to carry matches.” The film was shot with the

original script and is today a classic.

Douglas later would hire Kubrick to replace Anthony Mann as

director of his 1960 epic Spartacus. With an all-star cast that included Lawrence

Olivier, Jean Simmons, Charles Laughton, Tony Curtis, and Peter Ustinov as well

as Douglas in the lead role as the Roman Empire-era slave Spartacus, the $12

million film would win four Academy Awards and become a huge box office success

for Universal Studio. However, Kubrick hated working under studio and Douglas’

own restrictions, and Douglas would never forget how Kubrick was willing to

steal screenwriting credits from HUAC blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo.

Douglas’ decision to credit Trumbo on the big screen effectively restored

Trumbo’s career and brought an end to the dreaded blacklist that had ruined so

many lives and careers.

Douglas recalled the discussion he, producer Edward Lewis,

and Kubrick had about screenwriting credits for the film. “Use my name,” Kubrick

told them.

“Eddie and I looked at each other horrified. I said,

`Stanley, wouldn’t you feel embarrassed to put your name on a script that

someone else wrote?’ He looked at me as if he didn’t know what I was talking

about. `No.’ He would have been delighted to take the credit. … Stanley is not

a writer. … All this proves that you don’t have to be a nice person to be

extremely talented. You can be a shit and be talented and, conversely, you can

be the nicest guy in the world and not have any talent. Stanley Kubrick is a

talented shit.”

Kubrick, the lifelong lover of books who couldn’t write,

would go on to a heralded career as a director but one haunted by his obsession

with being the “auteur” who bears sole responsibility for a film and shadowed

by the same treatment he gave writer Jim Thompson in The Killing.

“Even then a self-styled auteur,

Kubrick was notorious for his cavalier use of writers,” Woody Haut writes in

2002 book Heartbreak and Vine: The Fate

of Hardboiled Writers in Hollywood. “Some authors would buy into the

Kubrick myth to such a degree that they would come to thank the director for mistreating

them.”

Writer Calder Willingham would get similar treatment in his

work with Kubrick on Paths of Glory

as would Terry Southern on Dr.

Strangelove (1964). Gustav Hasford’s book The Short-Timers became the basis for Kubrick’s 1987 war film Full Metal Jacket. The author also

worked with Kubrick and writer Michael Herr in crafting a script out of the

novel. A little known writer of a little known book with no agent or lawyer,

however, he only met Kubrick in person once and was relegated to communicating

with him only via phone, fax, or e-mail while Kubrick and the better-known Herr

worked more intimately together.

Both Herr and Kubrick’s biographer, Vincent LoBrutto, tend

toward hagiography in their books about the director, but Hasford’s dissatisfaction

with his treatment was obvious when he showed up unexpectedly on the set of Full Metal Jacket during filming. “I

wanted to see in fact whether the film was being made,” he said later in an

interview. “I was contemplating legal action at the time, and it would’ve been

pointless if there were no movie.”

Hasford won equal screenwriting credit with Kubrick and Herr

on Full Metal Jacket but it took a

small war to get it. “In the cynical world of L.A., where show ‘biz’ deals are

conducted in the back alleys of cocktail parties like self-parodying out-takes

from a comedic film noir, you might want to interject this lively note of

(transitory) optimism,” he later wrote. “I won my credit battle with Stanley. I

beat Stanley, City Hall, The Powers That Be, and all the lawyers at Warner

Bros., to and including the Supreme Boss Lawyer. As a little Canuck friend of

mine would say, I kicked dey butt.”

Michael Herr stopped speaking to him as a result, however.

Kubrick’s treatment of Jim Thompson left the writer scarred

for life. “That Stanley Kubrick `cheated’ him out of his credit on The Killing became another of Thompson’s

personal myths in the sense that for the rest of his life he rehearsed his

grievance to all who would listen,” Robert Polito writes in his biography of

Thompson. “His `betrayal’ by Kubrick is an anecdote that everyone who knew him

after 1955 can recite.”

Although Thompson’s family insists that the writer took his

case to the Writers Guild and won concessions plus the opportunity to work on

the Harris-Kubrick production of Paths of

Glory, Polito challenges that story, pointing out that Thompson didn’t join

the Writers Guild until two years later. Nevertheless, Thompson didn’t let

Kubrick’s betrayal prevent them from indeed working together on Paths of Glory, for which he did receive

joint credit with Kubrick and Calder Willingham for the screenplay.

James Harris insisted that Thompson only deserved his

“additional dialogue” credit, that the writer didn’t deserve more credit for

the script. Associate producer Alexander Singer, however, disagreed, telling

Polito that Thompson was “the person who wrote the script.”

In his 1999 book Eyes

Wide Open, a sharp critique of the director from a writer who’d worked with

him on his last film, Eyes Wide Shut

(1999), screenwriter Frederic Raphael describes Kubrick as a gifted director

with no ability to write. “Longing to deserve the accolade of auteurship,

directors often seek to append their names to the writing credits. Their habit

is to be empowered to embellish scripts which they were powerless to begin.”

Kubrick, with all his love for literature, had little

respect for screenwriters, Raphael writes. He recalled a conversation he once

had with Kubrick who told him the following: “No writer who’s really good is

ever going to invest his full ego in work that some other guy is going to come

in and direct. It’s a psychological impossibility.”

Nonetheless, The

Killing “ranks … among (Thompson’s) crowning accomplishments,” Polito

writes, while also marking the emergence of one of Hollywood’s greatest modern

directors. Thompson never became a Hollywood insider. “Jim Thompson loved the

idea of Hollywood, especially the old Hollywood that endured around such

vintage establishments as the Musso & Frank Grill—Hollywood’s oldest

restaurant, a dark, woody chop house, fortified with two matching bars, on Hollywood

Boulevard.”

Kubrick eventually left Hollywood and moved to England to

make his movies. However, he was in many ways the embodiment of a new

Hollywood--brilliant, creative, and perhaps a bit ruthless, words that could

also be used to describe his first great film, The Killing.

_Lewis%20Hine.jpg)