The article below from Labor South's Joseph B. Atkins appeared in the

January 5, 2022, edition of Quinn Hough's amazing and innovative online film

magazine, Vague Visages, under the headline "The Light of Human

Love and Community: On 'Moontide' and 'Port of Shadows'". It deals with

the 1942 film Moontide, released 80 years ago next month, and the 1938

French film Port of Shadows (Le Quai des brumes), both starring

French actor Jean Gabin and dealing with working class lives. They provide a

fascinating study into the different approaches to filmmaking and storytelling

in Hollywood and Europe in the late 1930s and early 1940s, a difference that

still exists today.

(A scene from Port of Shadows with Jean Gabin to the right)

A change of heart comes to French itinerant seaman and

dockworker Bobo as he sips his whiskey with a female regular at the Red Dot

Inn. His wandering is over. He’s going back to his ramshackle barge on the

California coast, back to Anna, someone once as lost as he was but now a woman

who loves him as much as he loves her. So what if a “gypsy is dying, and a

peasant is being born.”

It’s a decision that will

prompt a deadly encounter with his jealous crony Tiny, but in the end Bobo and

Anna marry. He’ll carry her across their humble threshold to live happily ever

after.

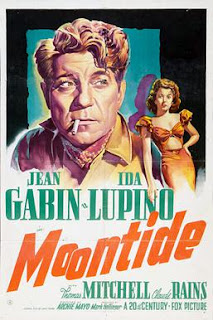

20th Century Fox producer Darryl F. Zanuck saw the

role of Bobo in the 1942 film Moontide—this

April marks the 80th anniversary of its release--as the perfect vehicle

to Hollywood stardom for acclaimed French actor Jean Gabin. No way was the

film’s hero, a potential Gallic Clark Gable, going to die at the end. No sad

ending for Moontide.

(To the right, a scene from Moontide with Jean Gabin to the right)

What a contrast is the ending of another great Gabin film

that came out just four years earlier, Port

of Shadows (Le Quai des brumes). In

this cinematic high point of French “poetic realism,” Gabin’s character Jean is

also a wanderer who in the end returns to his equally lost lover Nelly. That

act, however, leads to his death at the hands of his cowardly nemesis, the

gangster Lucien.

Moontide and Port of Shadows offer a fascinating

study into key differences in Hollywood and European filmmaking and

storytelling during the 1930s and early 1940s, a time when the studio system

reigned supreme in Hollywood and war loomed heavily over the European continent.

Those differences weren’t ironclad—films had both happy and sad endings on both

sides of the Atlantic. Still, they existed and continued to exist in the coming

decades despite the overarching influence of commercialism in all cinema.

In Port of Shadows,

Gabin’s Jean is an Army deserter in the port city of Le Havre who fatefully encounters

the cabaret dancer Nelly, played by Michèle Morgan, at Panama’s, a lonely,

seaside bar on the ragged edge of the city.

In

Moontide, Bobo

encounters Anna, played by Ida Lupino, as she attempts a watery suicide. He saves

her life and takes her back to his barge, where she’ll eventually find meaning

in life again. Her backstory remains a mystery. Tiny, played by Thomas

Mitchell, dismisses her as a “hash hustler”. She was a prostitute in the book

that inspired the film. Soon she and Bobo fall in love.

Both films are suffused in portside fog and shadows, a

dreamlike, highly stylized world where crime and danger lurk in those shadows.

In each film a loyal dog follows the protagonist, instinctively growling at

Tiny in Moontide and at the duplicitous

Zabel in Port of Shadows. Zabel is Nelly’s

godfather whose lust for her drives him to murder.

A bar is important to the action in each film, the Red Dot

Inn in Moontide, Panama’s in Port of Shadows. In each film, Gabin’s

character leaves his lover behind but then returns to her. Each film features a

waterfront philosopher who makes observations about life and love—Claude Rains’

Nutsy in Moontide and Robert Le

Vigan’s painter Michel in Port of Shadows

before he drowns himself. The backstories of several key characters in both

films are simply missing.

However, the similarities break down in the hearts and fates

of Bobo and Jean. Bobo is a hard-drinking, hail-fellow-well-met kind of guy who

even offers to help to his feet the man he just cold-cocked in a bar fight.

Jean is a brooding war veteran with a chip on his shoulder, a soldier who saw

enough death in “Tonkin” to abandon his outfit.

The most striking contrast in the two films, however, comes

at the end with the fates of the two wanderers. Unlike Bobo’s happy reunion

with Anna, Jean’s return to Nelly provides Lucien an opportunity for revenge

for Jean’s shaming of him with slaps to the face in front of not only Nelly but

also his fellow gangsters.

As did another Marcel Carné-directed film, Le jour se lève

(1939), Port of Shadows, both written

or co-written by the poet of poetic realism, Jacques Prévert, showcased Jean Gabin’s ability to

speak volumes with a simple stare, a curl of the lip, a wordless shrug of the

shoulders. Gabin “at his best doesn’t need any dialogue,” film historian Foster

Hirsch has said. Both Carné films reflected the somber mood of a nation

and a people facing the specter and subsequent reality of Nazi occupation.

In fact, the roots of Port of Shadows

can be traced to the Neubabelsberg studios of the giant German film company UFA

(Universum-Film AG), where initial work was done before Hitler’s propaganda

minister, Dr. Josef Goebbels, rejected it as too dark and decadent. Ironically

the great French director Jean Renoir would later dismiss it as a “fascist”

film. Only after Carné and Prévert

brought it back to France were they able to make the film they wanted to make.

Based on a novel by Pierre Mac Orlan in which the action

takes place in Paris’ Montmartre and the Lapin Agile cabaret, not in Le Havre, Port of Shadows “was a fairly

revolutionary film, both in spirit and in form,” Carné says in his 1996 autobiography. “In

that era the theaters were filled to the brim with comedies, musical or otherwise,

overflowing with bright sunshine and crawling with extras. And here I was with

my empty nightclub, my fog, my grisaille, my wet pavements, my streetlamps.”

Assembling a team that included supporting cast members Michel Simon

as Zabel and Pierre Brasseur as Lucien, Alexandre Trauner on set design, Eugen

Schüfftan as cinematographer, and music by Maurice Jaubert, Carné created a

masterpiece that was attacked by the Mussolini press at the Venice Film Festival

but which nevertheless won a Golden Lion award for the director. “Port of Shadows possesses nearly all the

qualities that were once synonymous with the idea of French cinema,” Luc Sante

writes in the Criterion Collection edition of the film. “The philosophical

gravity of peripheral characters, the idea that nothing in life is more

important than passion—such things defined a national cinema that might have

been dwarfed by Hollywood in terms of reach and profit but stood every inch as

tall as regards grace and beauty and power.”

Decades later American film critic Pauline Kael would call Port of Shadows “a breath of fresh air

to American filmgoers saturated with empty optimism.”

(To the right Jean Gabin)

Gabin’s earlier success in films like Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko (1937) and Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1937) got 20th

Century Fox’s attention, and its publicity wing pulled no stops in promoting him

as a French “hunk” primed to break the hearts of “dreamy readers of lonely

hearts columns,” in the words of Gabin biographer Joseph Harriss,

Arriving in America along with a wave of other French émigrés in

the late 1930s--like fellow actors Michèle Morgan and Louis Jourdan, and

directors Renoir, Duvivier, and René Clair--Gabin quickly came under studio

control. His contract got him the studio’s top salary, but Hollywood also put

an Apache scarf around his neck, coiffed his hair, and put mascara on his

lashes. They got him a chauffeur and a yacht. He rented Greta Garbo’s house and

committed to intense English language lessons.

The trouble was Gabin’s terrible homesickness—he would only

make one more film in Hollywood before returning to fight with the Free French

Forces. Unlike fellow Frenchmen Charles Boyer and Maurice Chevalier, he never

really adapted to the land or the language. Europe clung to him, as did his

mistress Marlene Dietrich. At her wishes, he urged the studio to hire the

famous Austrian director Fritz Lang, another émigré, to direct Moontide. Lang only lasted a few weeks,

his departure welcomed by Gabin after the jealous Frenchman learned Marlene had

once been Fritz’s mistress, too. Archie Mayo took over directing duties.

Novelist John O’Hara and veteran Hollywood scribe Nunally Johnson

wrote the script for Moontide, which

was based on a novel by Willard Robertson. It was “a noirish film resembling

the poetic realism of (Gabin’s) recent films in France,” Harriss writes. Still,

this was Hollywood where filmmakers faced the sharp eye of censor Joseph Breen

and the studio’s razor focus on the bottom-line.

Plus, “what does a Hollywood studio, accustomed to creating artificial

stars, do with an actor whose charisma, not to mention box office success,

derives mainly from his authenticity?” Harriss writes.

(Mich

èle Morgan)

Port of

Shadows co-star Michèle Morgan didn’t fare much better in

Hollywood. Despite the luxury Hollywood offered—she would live in the same

Brentwood Canyon home that later was the site of the notorious Charles Manson

murders in 1969—she bristled at efforts to turn her into a French sex kitten, a

“phony product” in her words, at “how

much the studio was trying to make her into something she was not,” Harriss

writes. She eventually returned to Europe and enjoyed a highly successful

career.

Trouble haunted the making of Moontide.

Marlene, 40 now, was jealous of 23-year-old (and happily married) Ida Lupino.

Gabin didn’t like Zanuck or the script. Producer Mark Hellinger liked the

film’s darkness but insisted on a happy ending. Amidst it all, Gabin continued

having a devil of the time with the English language.

Moontide got mixed

reviews—critics said it was too slow--and didn’t score high at the box office

either. The New York Times’ Bosley

Crowther liked Gabin better than Moontide.

Marlene dismissed it as “an idiotic film” in her 1987 autobiography, and Gabin

biographer Harriss called it “an embarrassment” that forced Gabin to overact

with “whimsical faces, curiously thrusting out his lower lip to look fanciful while

spouting words of wisdom. … The grotesque result is Gabin doing an American

imitation of Gabin.”

Still, the film had its champions. Although one of film’s

most acerbic critics, Manny Farber called it “superb” and “a picture moving and

good” that depicts “wonderful movie love.”

Today, the tide has turned for Moontide. The criticisms and dismissals that made it “overlooked”

for many years are “a pity as the film is actually an intriguing mix of gritty

realism and stylish noir, a fascinating meeting of Europe and Hollywood and a

curious combination of aesthetic peculiarities and moving performances,” critic

Martyn Bamber wrote in Senses of Cinema

in 2018. Moontide stands today as “a

love story in a noir universe,” says film noir guru, publisher, and Turner

Classic Movies host Eddie Muller.

“You can understand why the film was not successful, but 65

years later it is fascinating,” Foster Hirsch said in 2017.

One reason Moontide

may not have resonated with American audiences in 1942 was that, despite the

happy ending, they weren’t used to the things it shared with Port of Shadows—the darkness, the dreamlike

world (Spanish artist Salvador Dali helped shape one hallucinatory scene

depicting a drunken spree by Bobo), the gloomy touch of foreignness that would

later become de rigueur in film noir.

(To the right, Ida Lupino in Moontide)

Writer and lecturer Robert McKee described the different

attitudes in Europe and Hollywood toward filmmaking and storytelling in his

classic 1997 book Story. “Hollywood

filmmakers tend to be overly (some would say foolishly) optimistic about the

capacity of life to change—especially for the better. Consequently, to express

that vision they rely on … an inordinately high percentage of positive endings.

Non-Hollywood filmmakers tend to be overly (some would say chicly) pessimistic

about change, professing that the more life changes, the more it stays the

same, or, worse, that change brings suffering. Consequently to express the

futility, meaninglessness, or destructiveness of change, they tend (toward)

negative endings.”

Surely the legacy of 20th century dictatorships,

wars, destruction, political and economic upheaval in Europe helped create a

sense of fatalism and the existential absurdities of human life.

In the United States, existentialism had to make way for

capitalism. Screenwriter and novelist Budd Schulberg points to this in his book

Moving Pictures, describing MGM titan

Louis B. Mayer’s filmmaking philosophy as early as 1920s Hollywood. “Mayer’s

credo was … to give the public what it wanted, right down to that lowest common

denominator: the twelve-year-old mind. Family pictures. Romance. Happy endings.

Movies could titillate, but in the end husband and wife, or estranged young

lovers, must be reunited. That was Mayer’s law. The moral standards of

middle-class America must be upheld.”

Of course, the bottom line was the foundation of Mayer’s

law.

“What we have in Hollywood is an artistic medium encased in

a business enterprise, and the business enterprise is considered more important

than the artistic endeavor,” screenwriter/director Abe Polonsky said in a 1998

interview.

Film critic Pauline Kael has also weighed in on the

influence of commercialism on how stories are told in Hollywood and what

audiences have come to expect from the movies they watch. “From the beginning, American film makers have

been crippled by business financing and the ideology it imposed: they were told

that they had an obligation to entertain the general public, that this was a

democratic function.”

For those film lovers like her who have sometimes wanted

more than what “commercialized Hollywood” might offer, Kael said, “Le Jour

se Lève and La Grande Illusion restored us.”

Recent films such as Netflix’s Worth in 2021 show that remnants of the old Hollywood formula

remain. A film about the government effort to compensate the wide range of victims

of the 9-11 attacks, Worth is in many

ways “an excellent film” but also a “frustrating” and “irritating” one because

in the end “it appears to retreat from the implications of the way it’s telling

its complex narrative,” film critic Matt Zoller Seitz wrote for RogerEbert.com reviews.

Worth offers a

classic narrative arc in which Michael Keaton’s Kenneth Feinberg turns away from

cynicism to a driven commitment to help victims regardless of their status in

society. The film ends with a list of Feinberg and his team’s successes in

pursuing that goal, as if the issue was largely resolved.

A sharp contrast to this conclusion is the ending of Michael

Moore’s 2007 documentary Sicko, in

which 9-11 victims have to go to Cuba to get the medical treatment they need

because they cannot get it in the United States.

“The reluctance to tear down restrictive storytelling

templates rather than merely jostle them a bit is of a piece with the film’s

refusal to really engage with the question of whether a CEO’s life is worth

more financially than a janitor’s,” Seitz writes about Worth.

Of course, as said earlier, the cinematic divide between

America and Europe isn’t ironclad. The New Hollywood films of the 1960s and

1970s broke from the old studio-driven formulas and “brought to the screen a

gritty new realism and ethnicity,” Peter Biskind writes in his 1998 book on the

era, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. More

recently, director Robert Eggers’ moody and dark film The Lighthouse (2019) with Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattison as two

lighthouse keepers hardly offers viewers a happy ending. The two become mad,

Dafoe’s character dies, and the film ends with Pattison’s character naked and

under assault by a flock of gulls.

(Harry Dean Stanton in

Paris, Texas)

Europeans still make films differently. Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas in 1984, for example, is

filled with iconic images of the American West—the desert, lonely Western

towns, endless highways—yet it is suffused with European sensibilities, from

Wenders’ direction to Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller’s camerawork, its slow

pace, sparse dialogue, sad and fatalistic ending still hard to find in most

Hollywood films.

As detailed in Emilie Bickerton’s 2009 book on the history

of the icon-breaking film magazine Cahiers

du Cinéma, European film hasn’t

been immune from the pressures of the bottom line. By the 1980s, even the once

“troublemaking” Cahiers du Cinéma, a magazine that helped launch

the French New Wave in film (ironically itself a movement that paid homage to Hollywood

masters like Howard Hawks, Nicholas Ray, and British-born Alfred Hitchcock), had

become “a mouthpiece for the market (with) the mind-numbing quality of an

up-market consumer report,” Bickerton writes.

Ultimately the way of storytelling in films can be

problematic on both sides of the Atlantic, McKee says. “Too often Hollywood

films force an up-ending for reasons more commercial than truthful; too often

non-Hollywood films cling to the dark side for reasons more fashionable than

truthful. The truth, as always, sits somewhere in the middle.”

Looking back at both Moontide

and Port of Shadows after the passage

of some eight decades, both films, as different and as similar as they are,

provide a satisfying cinema experience. Farber was right to call Moontide a “picture moving and good,”

one in which “a quality of human goodness and fraternity” is palpable despite

the dangers that also face the main characters. The filmgoer is glad when Bobo

and Anna get together, and that’s great if they do live happily ever after. Port of Shadows, as dark and sad as it

is in the end, deserves all its accolades.

In both films, the light of human love and community manages

to break through all that fog, all those shadows, and that light still burns

when we leave the theater and step back into our own world.