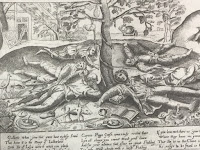

(A 1670 "Mapp of Lubberland", the imaginary isle where the lazy lower classes idle away their days)

Mississippi restaurants complained so loudly to Gov. Tate Reeves they can’t find people to work for $2.13 an hour plus tips that Reeves informed the federal government his state would no longer accept COVID-19 unemployment benefits for workers.

Philip Gunn, speaker of the Mississippi House of Representatives and Republican like Reeves, wrote the governor that restaurants and other businesses can’t get workers “to return to work because they earn more from combined federal and state unemployment benefits than their normal wages.”

So Mississippi joined fellow Southern states South Carolina, Arkansas, Alabama, and other Republican-led states in the South and beyond in denying workers the $300 per week benefits that the federal government had authorized as a result of the pandemic. Unemployed workers in Mississippi will have to live on the $235 a week the state provides.

Inherent in all of this is the utter contempt for average working class people that the patrician leaders of the Republican-dominated South have long had. The Republican Party is the party of the rich—the property-owning business class, CEOs, the country club set, the landed gentry. Republicans in the South today aren’t really very different from the Bourbon Democrats of the Old South—arrogant, paternalistic, ever suspicious of someone from the lower classes trying to sneak a free ride.

Even when Republicans cloak themselves in a kind of inverse populism, like Donald Trump, the contempt is still there, just under the surface, and it shows itself in their policies and actions, such as Trump’s eviscerating of the National Labor Relations Board during his administration.

Restaurant workers and retail workers were hit hard by the pandemic as businesses across the land shut down. Mississippi’s unemployment rate jumped from 5.8 percent in February 2020 to 15.7 percent in April 2020. Today it hovers just a little above 6 percent.

Despite a federal $7.25-per-hour minimum wage, restaurant workers typically work for as little as $2.13 an hour with the hope that tips can make up the difference.

“To ask people to go back to work for low wages instead of receiving a `living wage’ is asinine,” Democratic Mississippi Rep. Jeramey Anderson of Moss Point said in a tweet reported by the Mississippi Free Press. “Unemployment benefits are not the problem. Our failure to address low wages in our state is the real issue.”

In her compelling book White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, author Nancy Isenberg tears away at the lie that the United States is a essentially a class-less country where anyone with some gumption can succeed. “We need to stop thinking that some Americans are the real Americans, the deserving, the talented, the most patriotic and hardworking, while others can be dismissed as less deserving of the American dream,” she writes. “Class is as American as it ever was British.”

Isenberg writes of how 17th and early 18th century aristocrats like the British philosopher John Locke and the Virginia planter and diarist William Byrd II considered the lower classes such as those in the colony of North Carolina lazy, shiftless, contemptible, needing-to-be-ruled residents of what they called “Lubberland”.

Old attitudes die hard.

The media are as much to blame as greedy capitalists. Every issue that raises the spectre of class conflict in America is immediately sidetracked into an issue of race or of the narrow-minded prejudices and ignorance of the Great Unwashed. The utter frustration of their voicelessness in both the Republican and Democratic parties led many in those unwashed masses to vote for Donald Trump. Of course, he had no more intention of serving their interests than did Hillary Clinton.

Despite a blue-collar identity betrayed again and again in a political career of compromises, Joe Biden has thus far as president stepped up to the plate in support of working class people in his domestic policies. He’s shown sensitivity to their plight during the pandemic, expressed strong support for labor unions, and challenged rather than succumbed to Republican intransigence.

(To the right, the poet Dylan Thomas)

Workers in the South are showing some feistiness in face of the political hypocrisy that’s constantly dealt them. Sure, they lost big labor battles at the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, recently and at the Nissan plant in Canton, Mississippi, in 2017, but they’re not simply going gently “into that good night” the poet Dylan Thomas warned us about. They’re indeed raging “against the dying of the light.”

Nurses won a big battle in organizing at the Mission Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, last September. Workers at the Valley Proteins rendering plant in Bertie Country, North Carolina, are trying to organize. Miners at Warrior Met Coal in Alabama are on strike. Organizations like the Southern Workers Assembly and the United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers of America (UE) are sowing the seeds of a labor-conscious New South.

Sooner or later, enough eyes will open to the plantation mentality of political leaders like Tate Reeves of Mississippi that a change will come. The sooner the better.